A Re-post from our Friends at the Cloud Appreciation Society, authored by Wil Mauch:

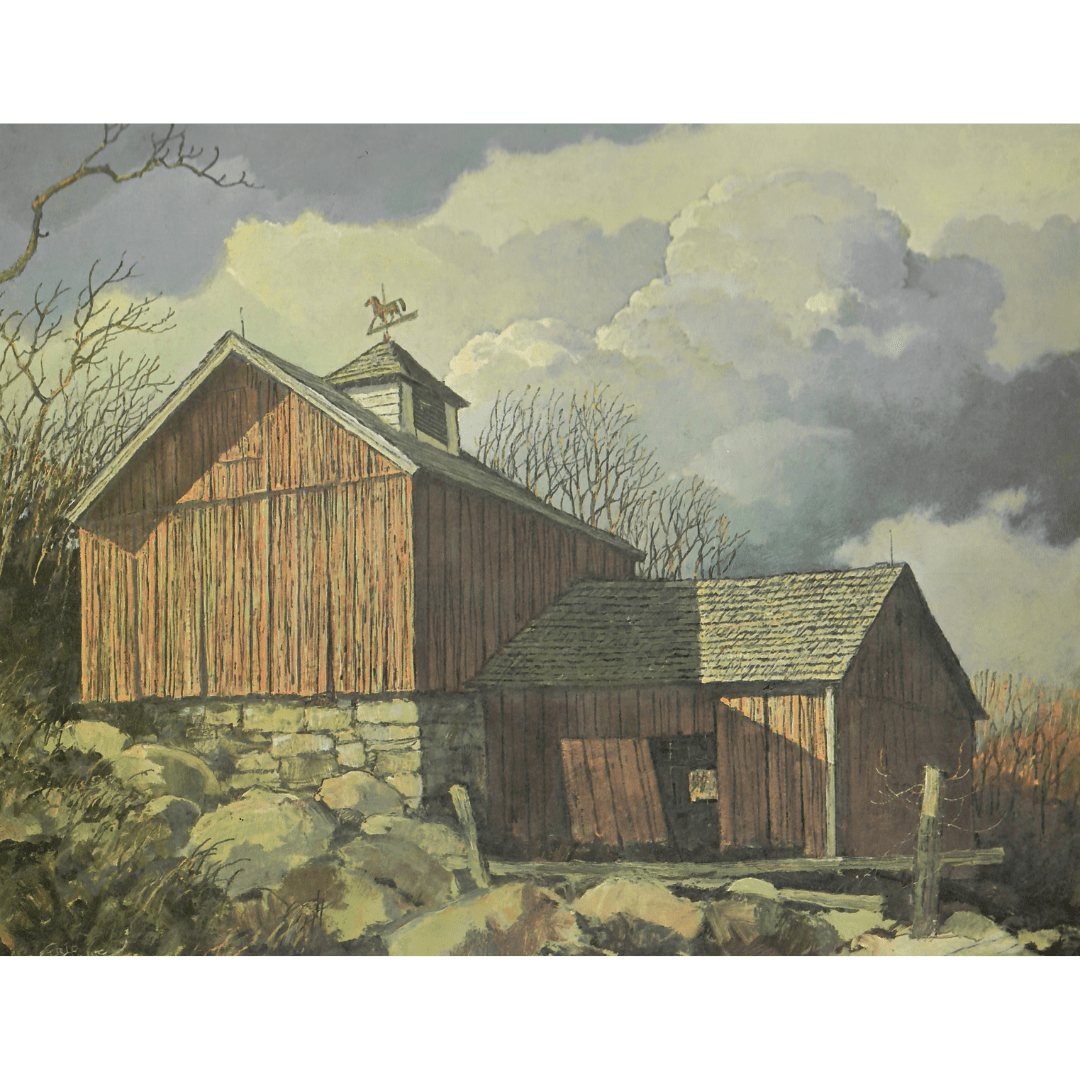

Eric Sloane (1905-1985) was an American fine artist, illustrator, and author. He is perhaps best known for his lavishly illustrated books on early American life and culture as much as for his paintings of rural America. No matter the subject matter – airplanes, the barns and stone fences of his beloved New England countryside, or the pueblos of New Mexico (for Eric painted them all) – it was always the sky and clouds that were the real subject matter for this self-taught artist. Sloane’s earliest years read like a Horatio Alger piece – born in New York City to wealthy parents who both died when Eric was young, leaving him with a million-dollar inheritance lost subsequently in the Great Depression. He flew with Wiley Post, sold his first “cloudscape” (a term he coined) to Amelia Earhart, created the Hall of Atmosphere for the American Museum of Natural History, and (at age of 71) was asked to paint a 58’ x 75’ mural for the entrance of the soon-to-be-unveiled Smithsonian Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. He worked incredibly hard, becoming an internationally recognized fine artist and best-selling author, all within his lifetime – much of his work devoted to encouraging people to look at the sky.

With thanks to Wil Mauch, the Cloud Appreciation Society, and The National Air and Space Museum for the image of Eric Sloane painting the Earth Flight Environment mural – Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum (NASM 9A11988).

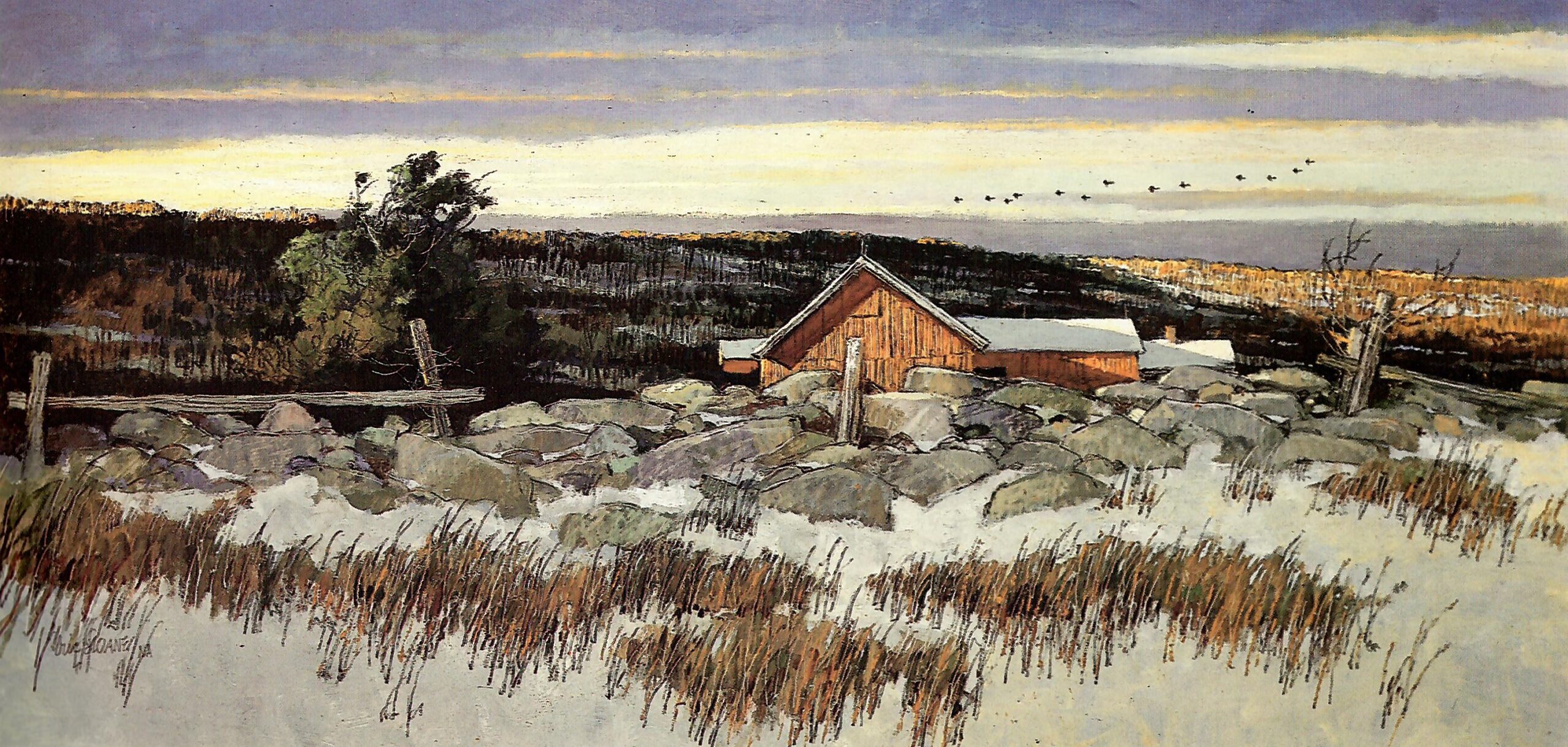

After the Second World War, Eric Sloane continued to draw illustrations and write articles for weather-related periodicals and magazines. In 1948 he became the Art Director for Weatherwise magazine, contributing dozens of illustrations and articles during his 5-year tenure with the periodical. Not content with publishing only in Weatherwise, Sloane had articles and illustrations published in Flying Cadet, Popular Science, Air Trails, Rudder, Science Digest, Flying, and Farm Quarterly during his Weatherwise years. In 1952, Eric Sloane’s Weather Book was published, one of seven more Sloane titles devoted to meteorology. His last meteorological title was For Spacious Skies (1978). Spring Sky is a masterful reflection of Sloane’s skills as a painter as well as his deep understanding of meteorology, light and shadow, color, reflection, and cloud formation.

This painting was chosen for the month of March in Eric Sloane’s 1976 For Spacious Skies Calendar. Eric had an incredible read of colors and shadows of a season. Not to mention a formidable understanding of cloud formations as they relate to conditions, season, time of day, and reflection of the light and color of the landscape. Here, the relative warmth of the spring atmosphere has built some cumulus clouds that will not turn into thunderstorms yet – those will come later in the summer.

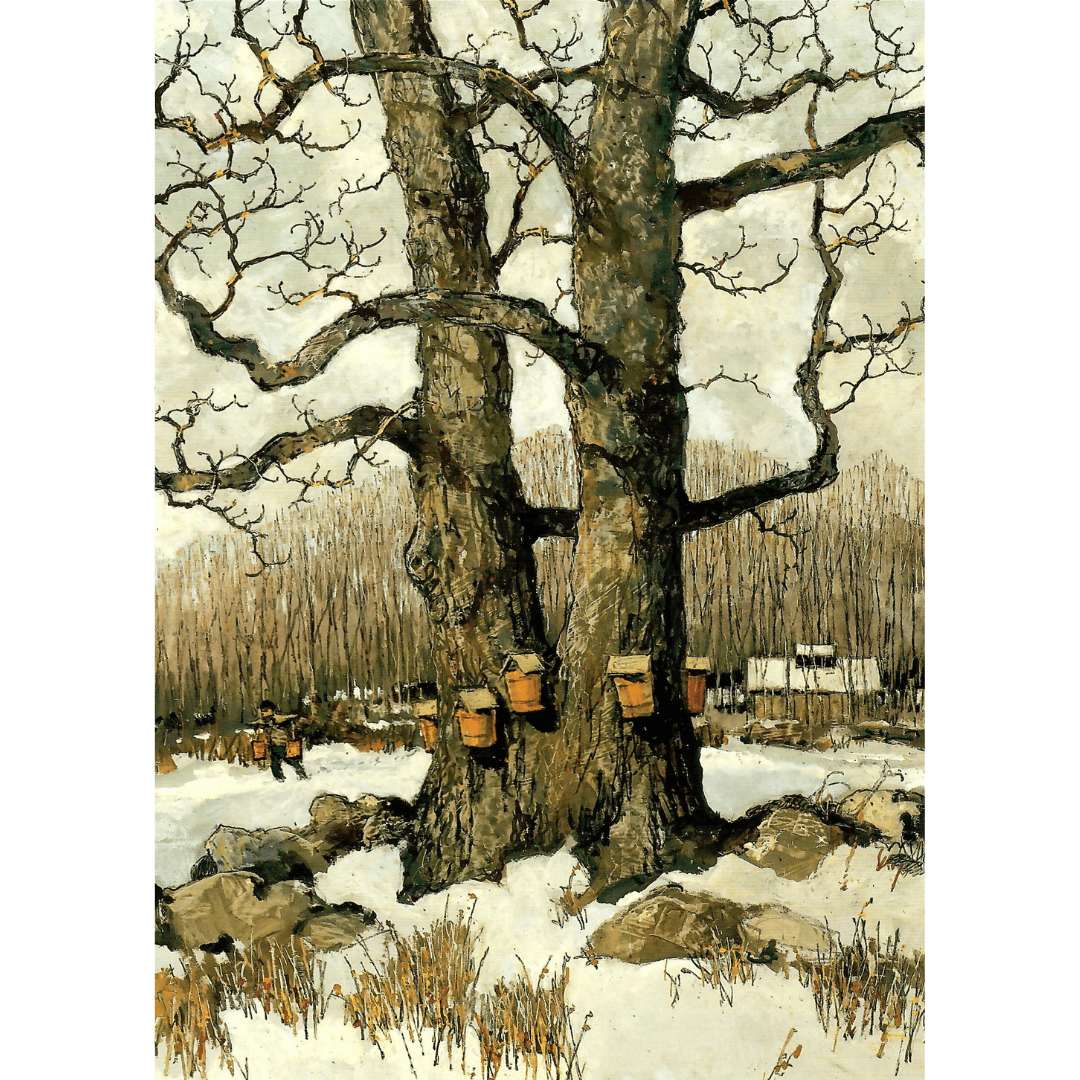

“Maple Sugaring Season” by Eric Sloane. Maple Sugaring season has arrived throughout much of New England. “Sugaring was hard work, but the American farmer made such a cheerful season of it that the whole family looked forward to sugaring, making it more play than work”. – from Eric Sloane’s Seasons of American Past (1958).

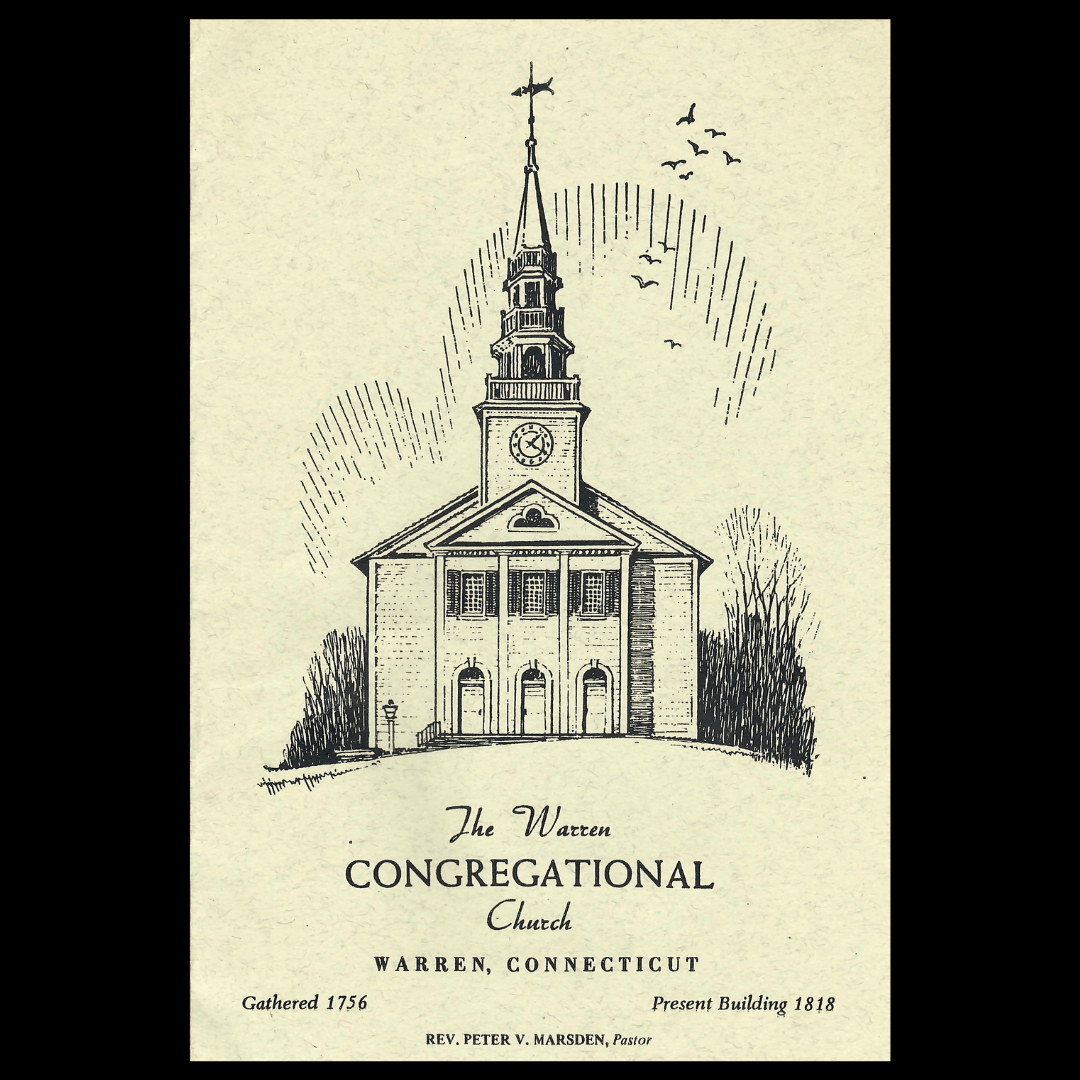

Eric Sloane died on this day in 1985, on the streets of the city in which he was born. His memorial service bulletin reveals a lot about the man – it is his illustration for the church on the cover, he was eulogized by David Armstrong, members of the Warren Volunteer Fire Company served as the ushers, and the parting hymn was “O Beautiful For Spacious Skies”. May he rest in peace.

“I hope that I might be quoted someday as having said: ‘The only value of age is that it gave time for someone to have done something worthwhile.’”

– Eric Sloane

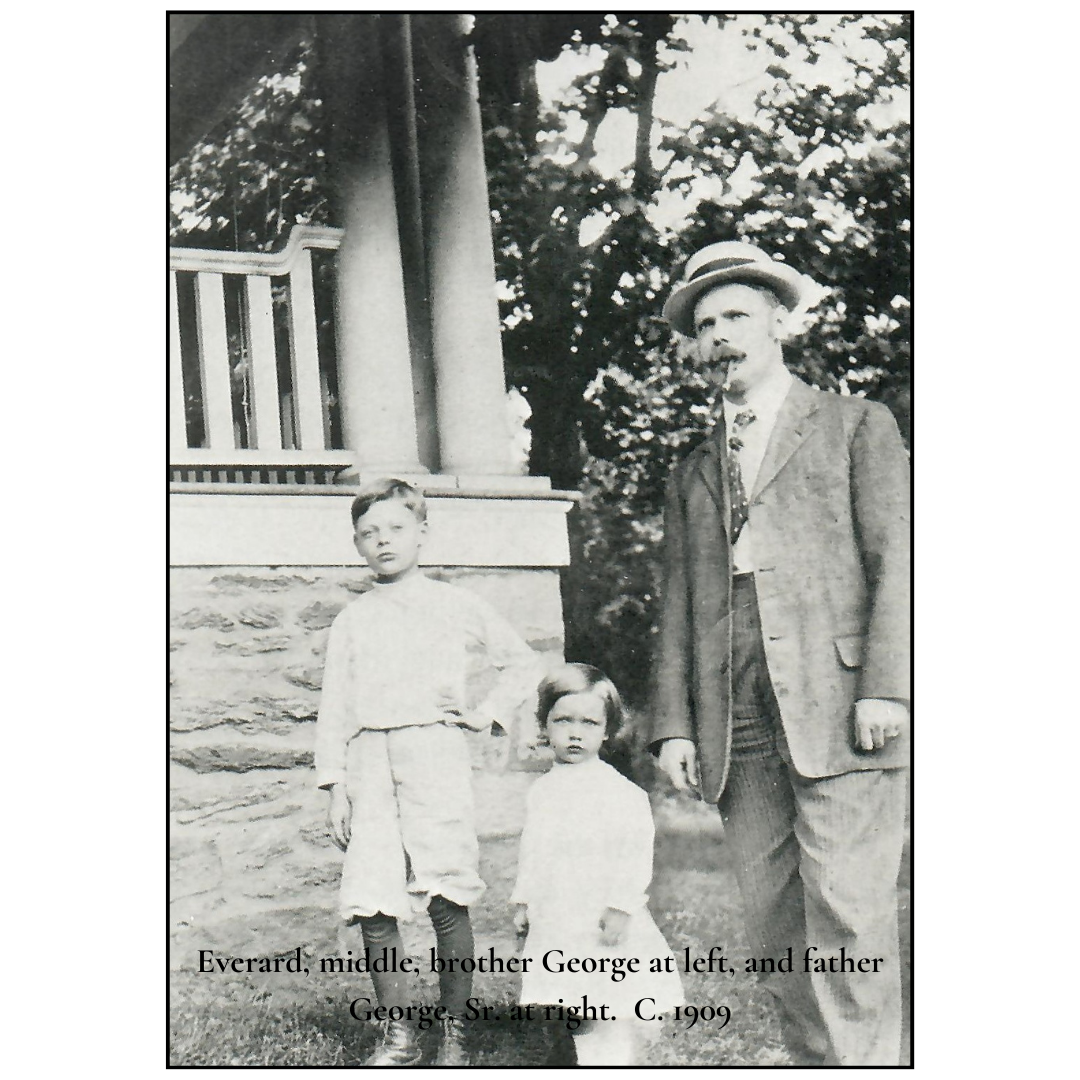

Born on this day in 1905 to a wealthy New York City Couple, Eric Sloane described his parents as having the least artistic tastes, which he credited to his growth as an artist. Interesting, as all three siblings became artists in their own right – Eric’s sister Dorothy became a folk artist, brother George became a landscape architect, and of course there is Eric, who would become an internationally known artist and author – all within his lifetime.

“I hope that I might be quoted someday as having said: ‘The only value of age is that it gave time for someone to have done something worthwhile.’”

– Eric Sloane

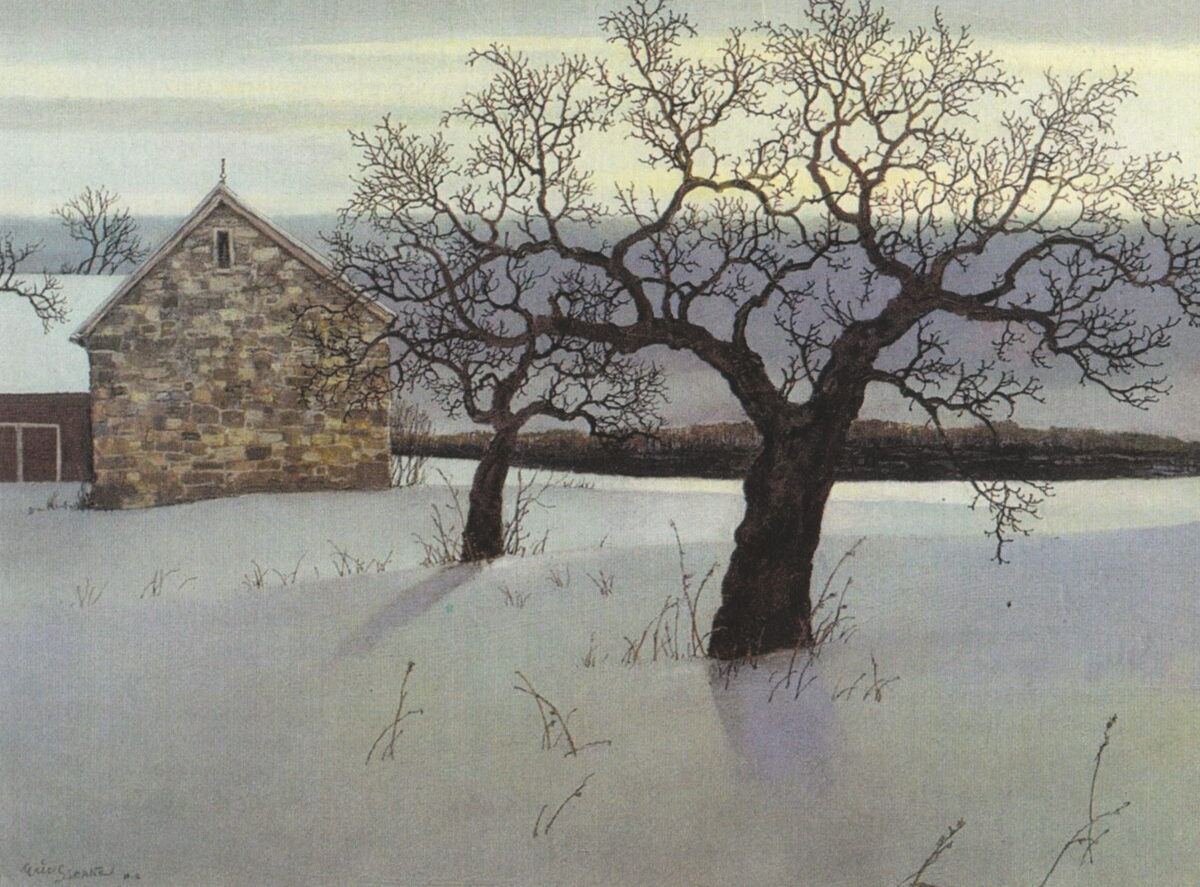

“Cloud ceilings during February are lower and flatter, causing dreariness during the day but letting the early morning and late setting sun peak beneath the cloud shelf with remarkable brightness…Groundhog Day (February 2nd) marked midwinter in the farming year of early times, when the woodpile should be exactly half exhausted., and the heart (“hearth” on old English) of the farmhouse was at the kitchen fireplace.” – Eric Sloane, “February”, from the For Spacious Skies Calendar of 1976.

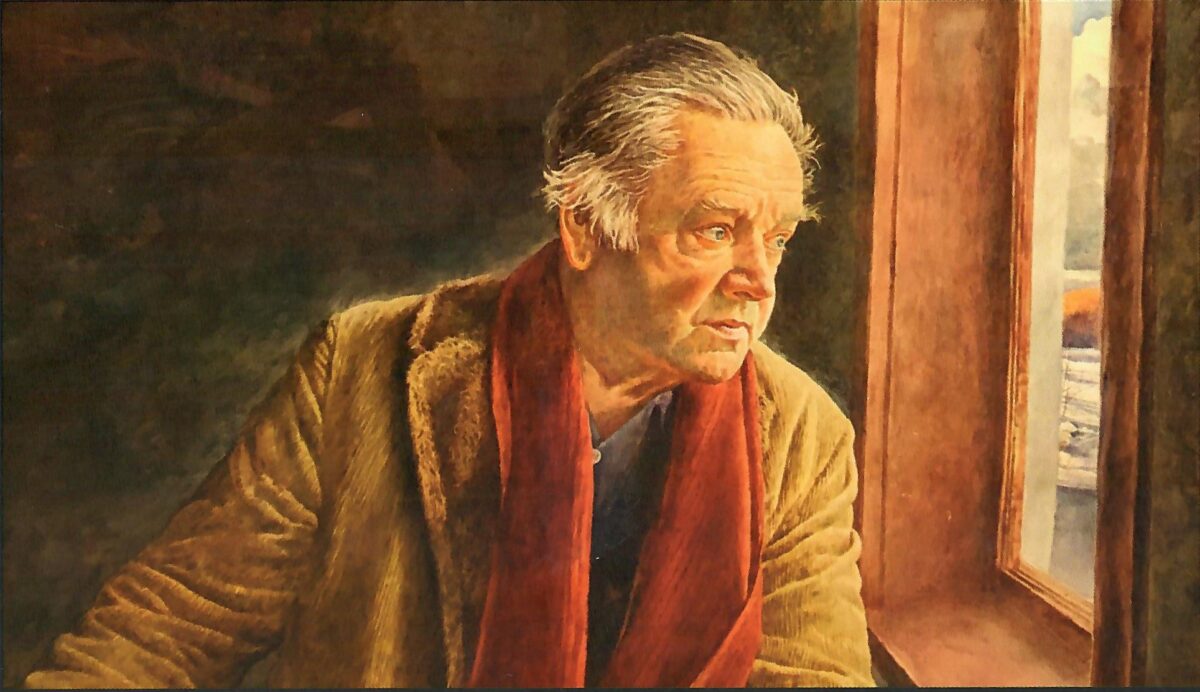

A portrait of Eric Sloane by David Armstrong (CT, PA 1947-1998). Criticized as “too somber”, Armstrong countered that “Eric was an unbelievably hard worker. He painted every day, morning to night. People didn’t see him struggling, wincing, staring out the window. He was never satisfied with his work.” Notice how Armstrong included that ever-important sliver of the New England landscape, visible through the window. Notice, too, how Armstrong rendered the clouds as an homage to his friend and mentor.

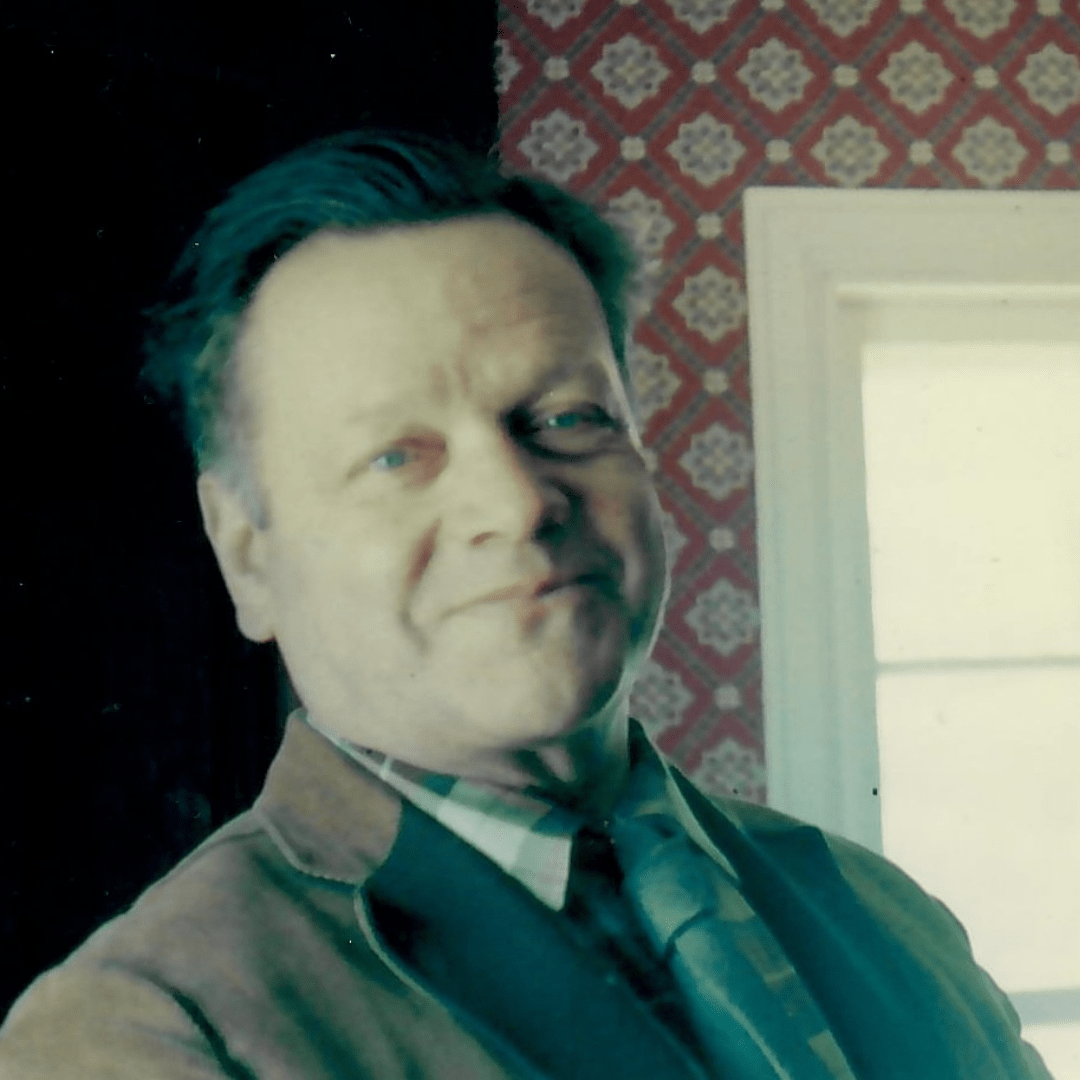

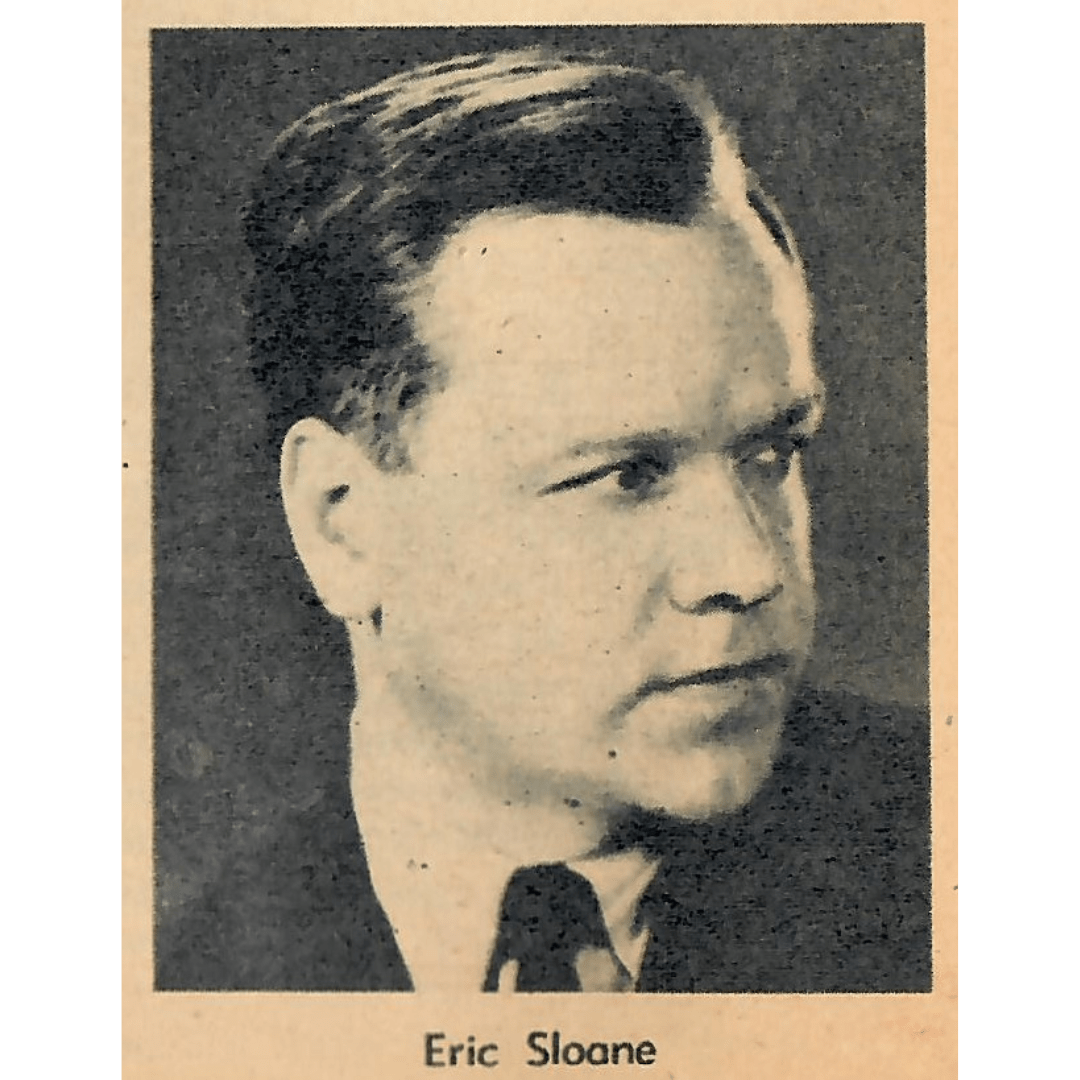

A photographic portrait of Eric Sloane, probably taken c. 1940, when the author/artist was 35 years old. During the Second World War, Eric created “thought pictures” for the U.S. Army Air Corps to help train pilots. The brass at the U.S. Army Air Corps had taken notice Eric’s first book, “Clouds, Air and Wind” (1941), and knew he was the choice to illustrate flying manuals. The June 1946 issue of Air Trails explained that “…Clouds, Air, and Wind took shape…This primer of weather has helped the Army and Navy flyers by means of his word pictures, not only to learn weather but to remember it. Its success gave Sloane the job of doing flight manuals at Wright Field. These were to explain the effects of flying upon the human body. He went through all the effects of high altitude, G-force, etc. and came out with a book of drawings called “Your Body in Flight”. German medical officers mentioned this book as being a gem of clarity and importance—something far beyond what the Luftwaffe had. There is no telling how many lives this manual saved by making our boys remember their flight physiology at altitudes where the mind is dulled by anoxia and extreme cold.”

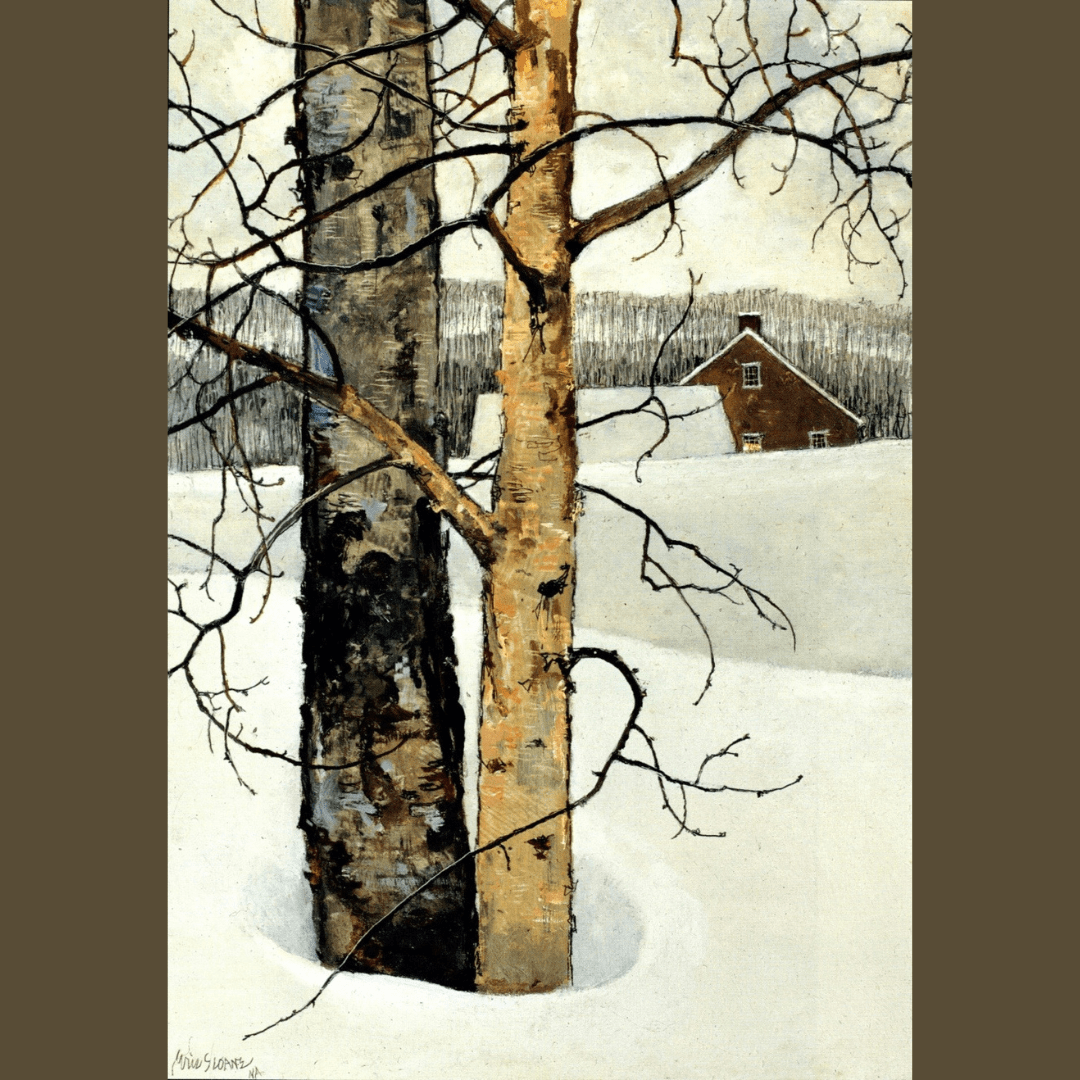

Trees in Winter by Eric Sloane, N.A. Notice how well the bark of the Birch trees is rendered – look closer and you’ll see how Eric used the flat side of a razor blade, working gently to pull the blade across the trunk horizontally to produce the effect of Birch bark. Eric also includes “Tree Wells”, the area around the trunks where the snow looks like it has melted. Indeed it has, as these wells are formed because sunlight has reached the trunks, warming and reflecting upon the snow that has come to rest nearest the trunk.

As we are in the month of January, this painting seems especially fitting. Titled January Sunset, at least until Eric Sloane saw the title. He attempted to correct the gallery, pointing out that the title should read January Sunrise. The gallery owner was unmoved, and indicated to Eric that it really shouldn’t make much of a difference. “I’d know the difference”, a perturbed Sloane wrote the gallery manager, “sunset clouds are usually cumulus or lumpy, a product of rising thermals from heated ground while sunrise clouds are flat stratus (as in my painting), the result of cold night air being pushed downward by the inversion of upper air heated by the rising sun”. Indeed, January is the month for cold night air.

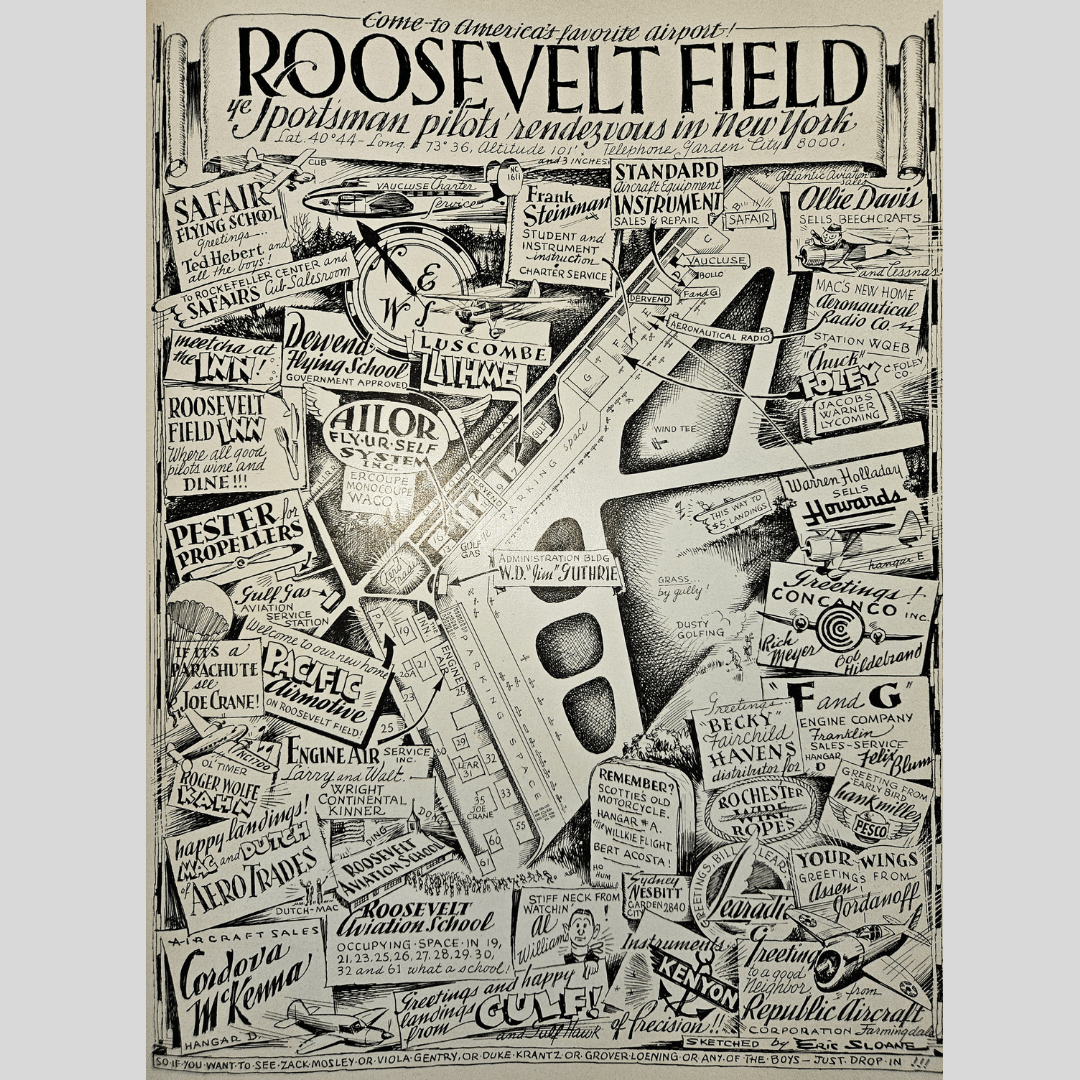

During c. 1935-1945, Eric Sloane created a number of aviation-related maps for various publications, including this one of Roosevelt Field for a 1941 issue of “The Sportsman Pilot”. These types of maps were always engaging to the eye. They are whimsical, yes, but to modern eyes also convey a great deal of information concerning the major players in early aviation.

Sloane filled these maps with prominent names and businesses partly to sell the finished product, which would have been a “stand alone” map. One can imagine that every individual and business would want to purchase at least one of these maps – not a bad sales strategy!

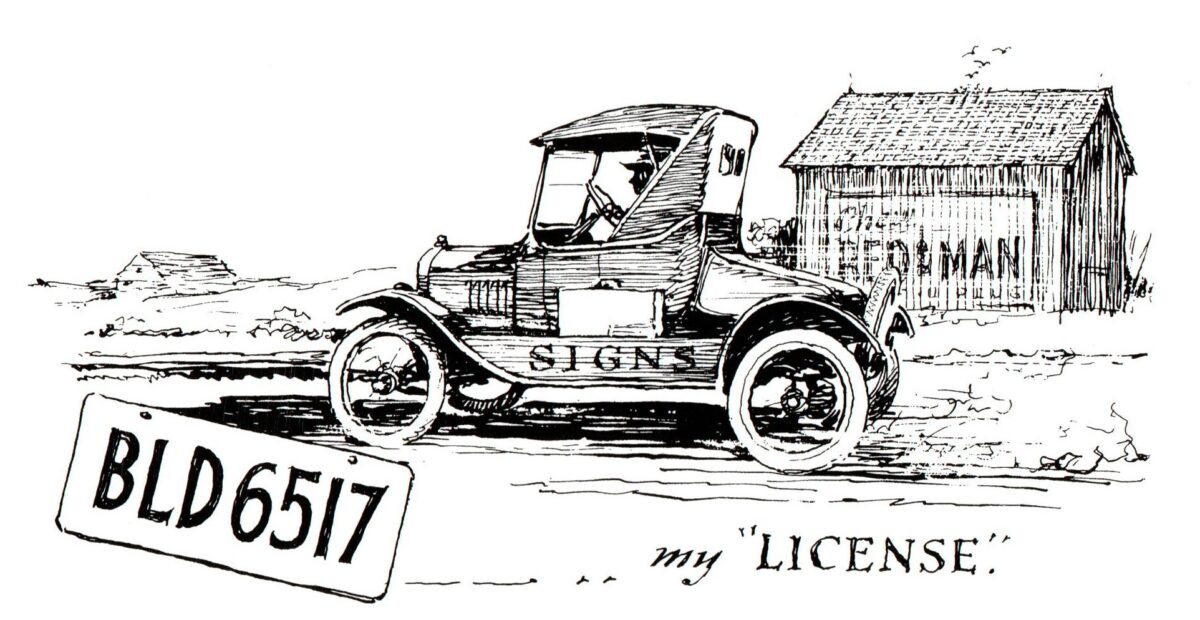

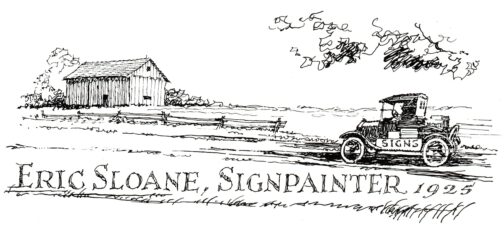

As a teen, Sloane ran away from home several times, often covering great distances. He once stole his father’s Model T Ford, forging the license plates in the process. He drove across much of the Continental Unites States, an escape that provided thousands of recollections to which an older Sloane would return in print and oil paints. He illustrated and painted along the way, trading menu lettering and decorations for meals, lettering windows and doors at hotels for rooms, somehow managing to keep enough fuel in the Model T. He also sketched and painted, most especially around Taos, New Mexico, by then an artist colony. When planning his return to New York City, Sloane decided that he would return as an artist.

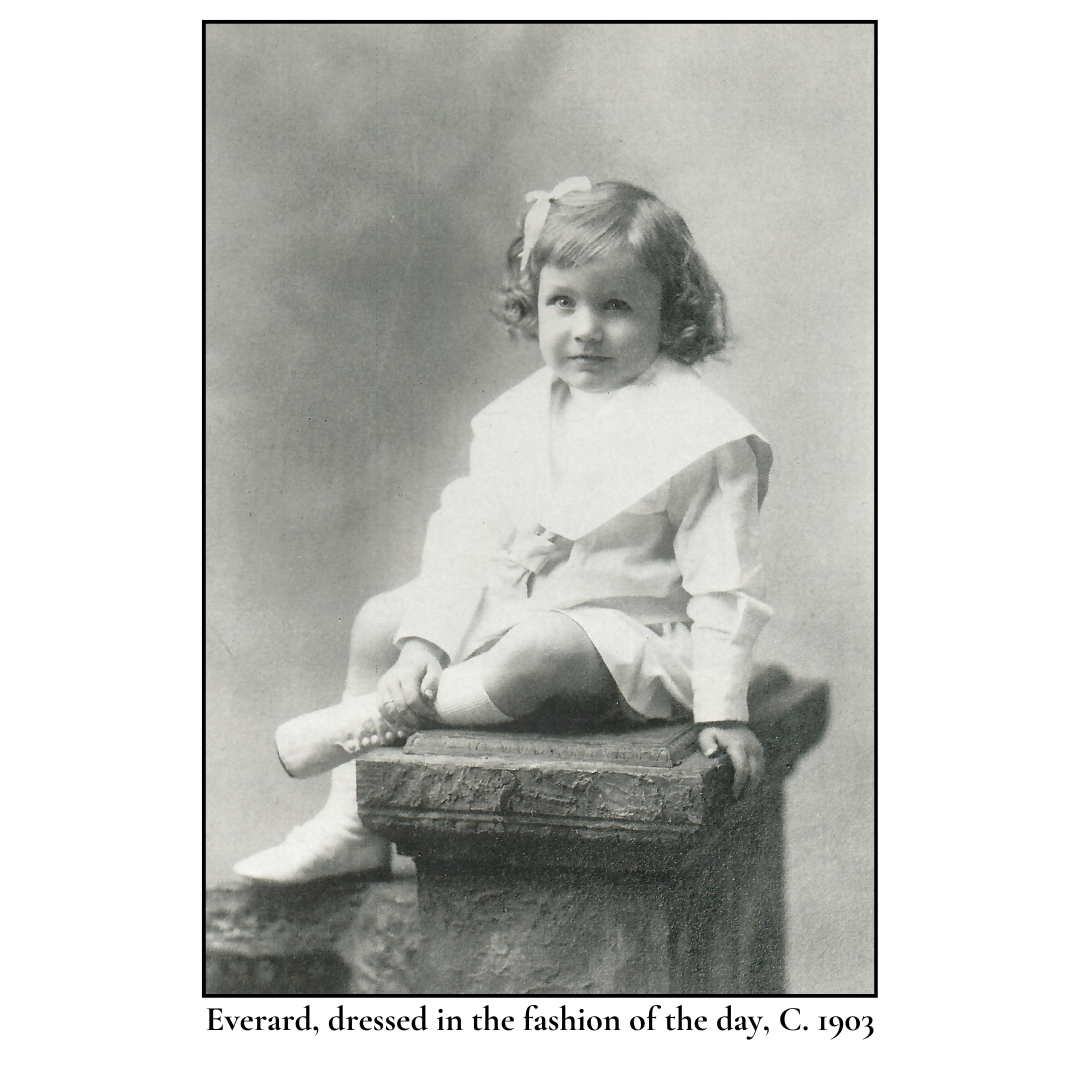

Born February 27, 1905, Everard Hinrichs – who later changed his name to Eric Sloane – was raised in a wealthy household to parents he describes as “…harboring the least artistic tastes”. The family summered on Halsey Island, Lake Hopatcong (New Jersey), and it seems clear that it was there that Eric’s artistic intuition began to flourish.

Eric’s sister Dorothy recalled Everard as “…mischievous and careless with his possessions (his own and other’s), but in the end he was lovable and always eager to please”.

It would seem that a future of familial wealth and relative leisure would grace George Jr., Everard, and Dorothy, but that was to be an illusion of “The Roaring Twenties” – the Great Depression that followed erased the family fortune, scattering the siblings and leaving Everard destitute.

Eric Sloane (1905-1985) was an American fine artist, illustrator, and author. He is perhaps best known for his lavishly illustrated books on early American life and culture as much as for his paintings of rural America. No matter the subject matter airplanes, the barns and stone fences of his beloved New England countryside, or the pueblos of New Mexico (for Eric painted them all) it was always the sky and clouds that were the real subject matter for this self-taught artist. Sloane’s earliest years read like a Horatio Alger piece born in New York City to wealthy parents who both died when Eric was young, leaving him with a million-dollar inheritance lost subsequently in the Great Depression. He flew with Wiley Post, sold his first cloudscape (a term he coined) to Amelia Earhart, created the Hall of Atmosphere for the American Museum of Natural History, and (at age of 71) was asked to paint a 58 x 75 mural for the entrance of the soon-to-be-unveiled Smithsonian Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. He worked incredibly hard, becoming an internationally recognized fine artist and best-selling author, all within his lifetime much of his work devoted to encouraging people to look at the sky.